Why handling rare books can mean the gloves come off

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Elizabeth Gramley, Rare Books Intern

August 24, 2023

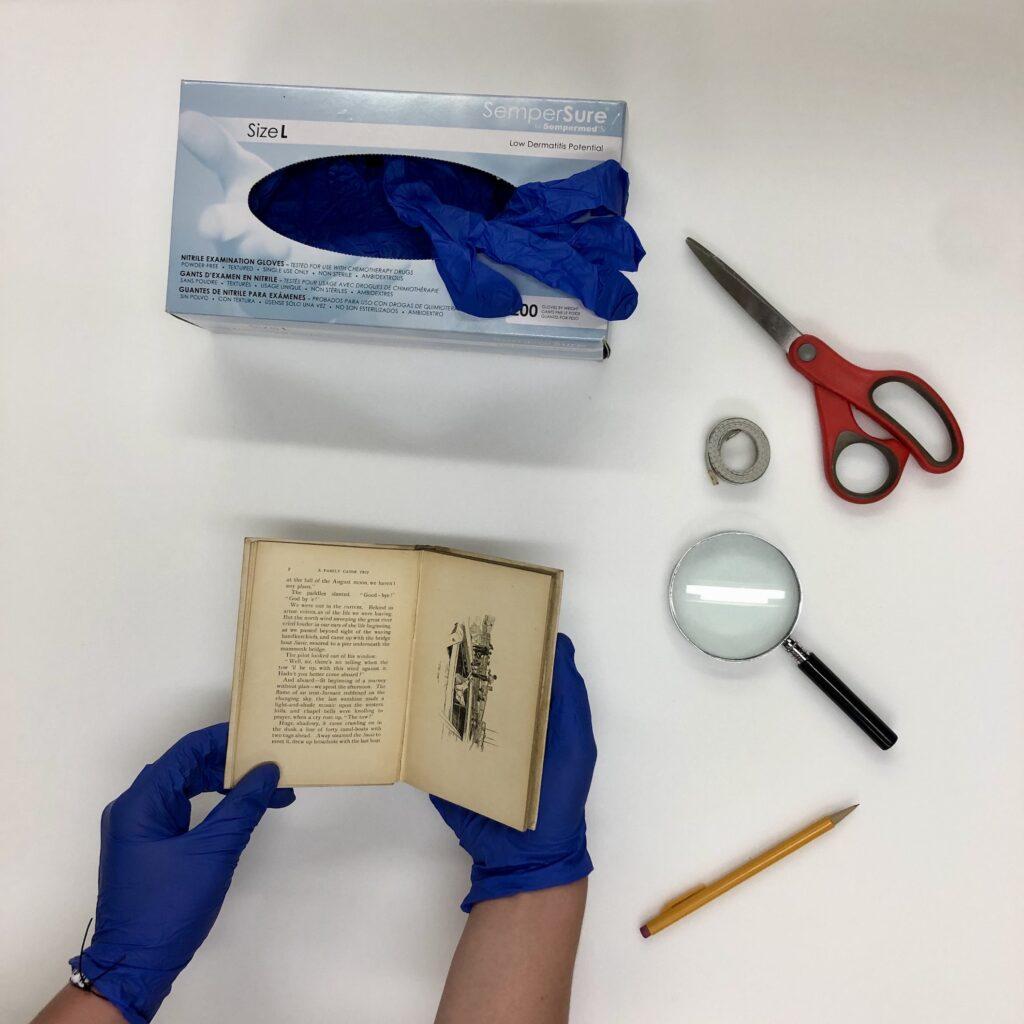

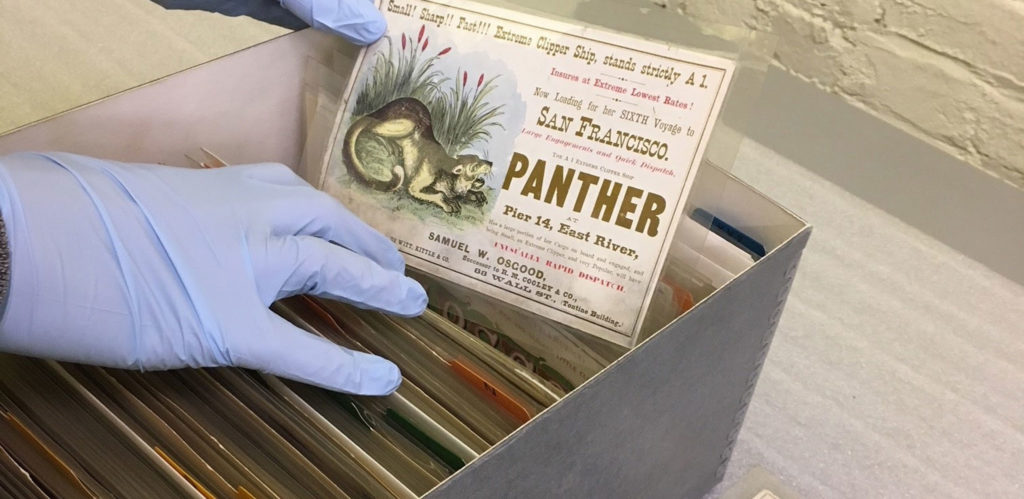

In my three months as the Rare Books Intern at the South Street Seaport Museum, I’ve settled into a daily routine. As soon as I get to the collections storage where the Museum’s rare books are kept, I sit down, put on a pair of blue nitrile gloves, and begin carefully unpacking, assessing, and documenting boxes of books.

The Seaport Museum has an extensive collection of books published prior to 1900, from dramatic sea novels to treatises on how to read steam gauges. The institution began collecting books, historic artifacts, and works of art at its founding in 1967, though there was no official distinction between rare books—preserved in part for their artifactual value—from reference books to be lent.

Over the next several decades, the book collections grew to over 12,000 volumes, but it was not until 2011 that significant attention was paid to the publications that were considered rare (prior 1900). The Museum’s Archivist and Librarian at the time, Carol Clarke, estimated that there were approximately 1,000 rare books in the collection.

In 2019, the Rare Books Collection was packed up (in over 100 boxes!), relocated to collections storage for better care and cataloging purposes, and in the Fall of that year, an in-depth inventory of the collection began.

Over the past four years, several interns at the Museum have undertaken the work of unpacking these boxes and rediscovering their contents. The spreadsheet tracking the collection now has more than 1,200 entries, already well above the initial estimate of the collection’s size, with more than a dozen boxes remaining.

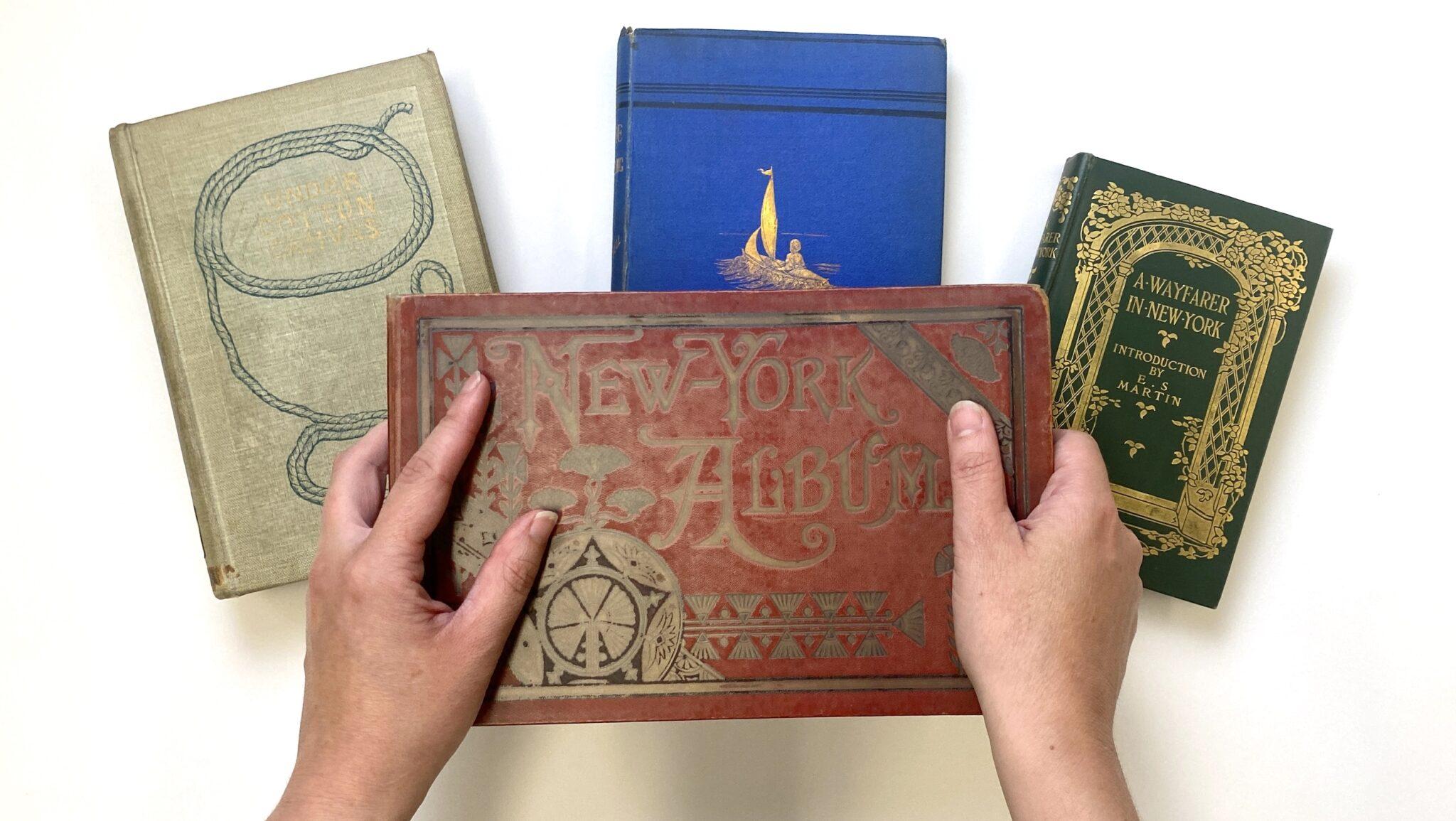

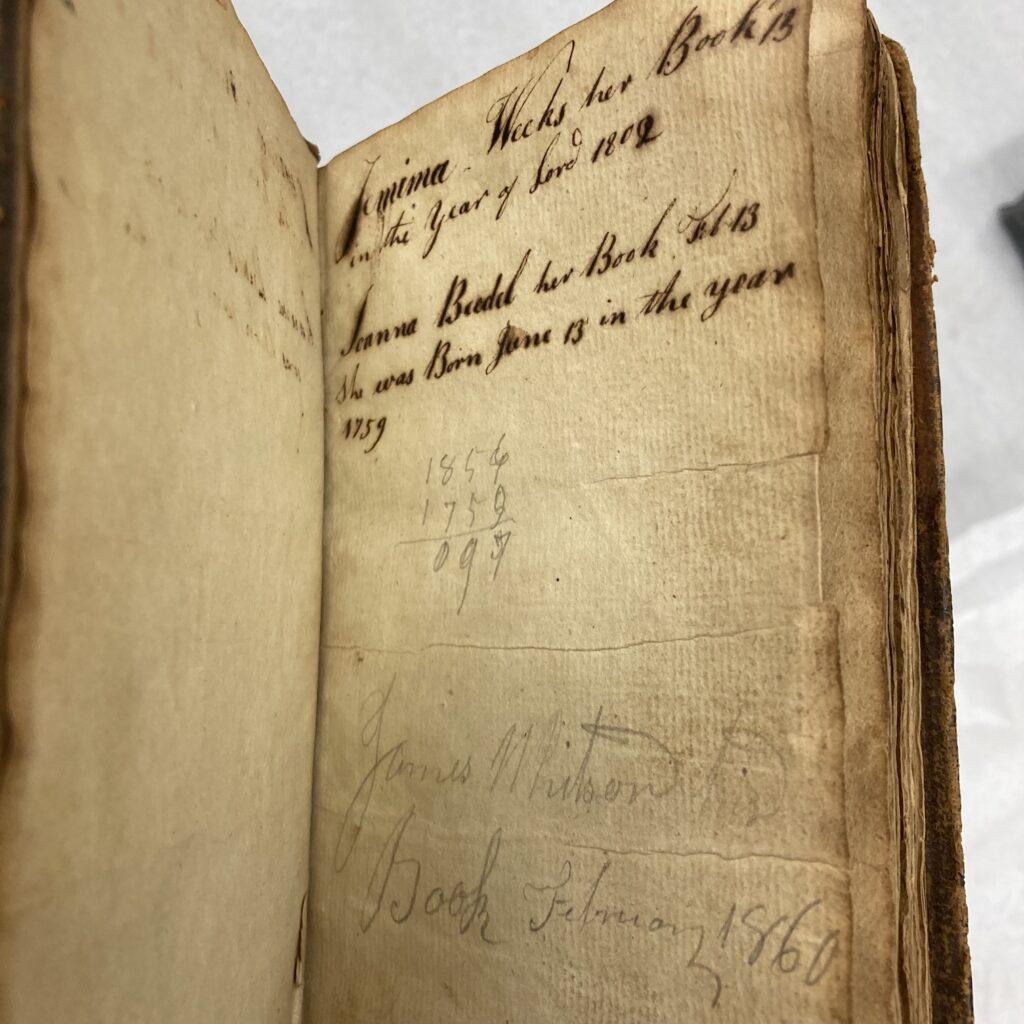

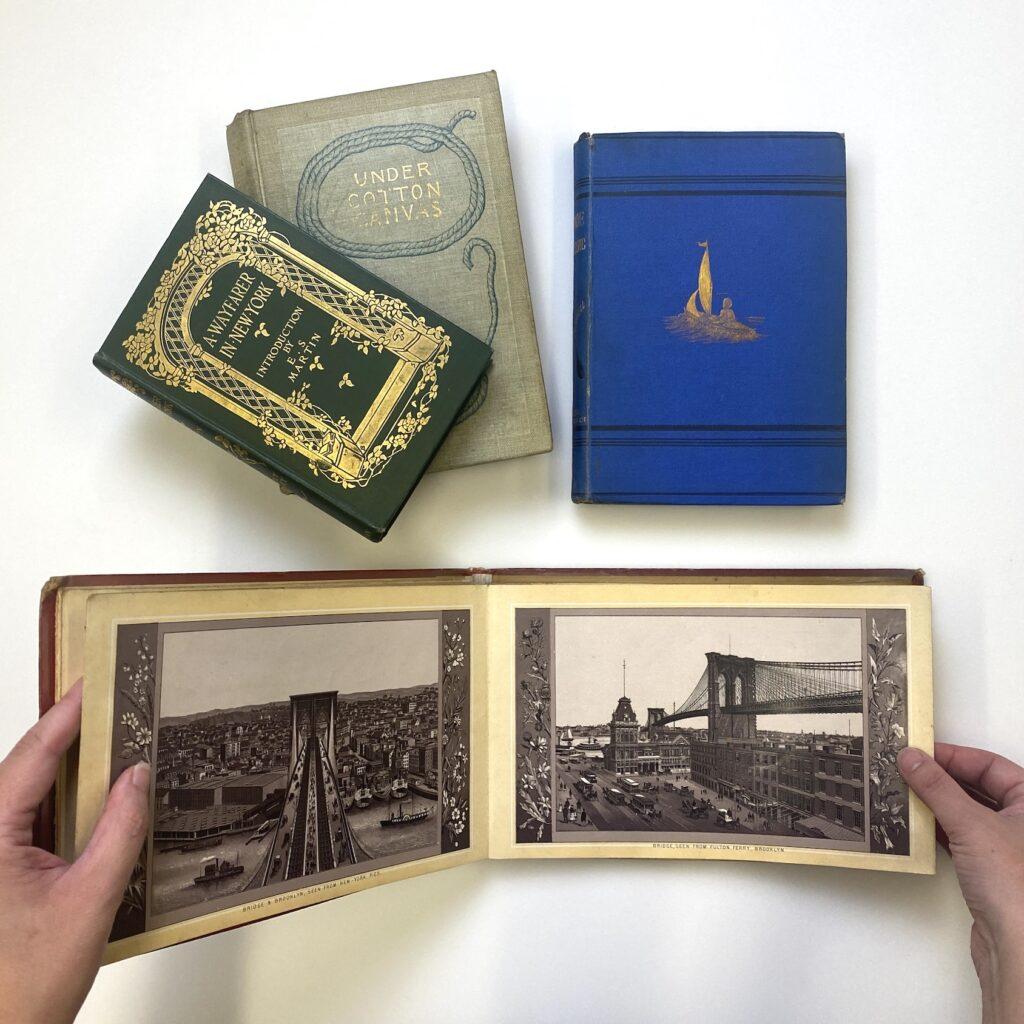

Although we have an inventory list of titles in the boxes, each box is still full of surprises. Some of my favorite finds have included a book published in 1797 with annotations noting the birthdates of a few of its owners, a yearbook/literary magazine from Stevens Institute of Technology with numerous creative, unusual, and odd illustrations, and countless books with page-long titles describing disasters at sea—a bit of proto-clickbait. The collection is as varied as it is vast, and so it is imperative that each book is treated with care and caution. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean literal white glove service for the collection.

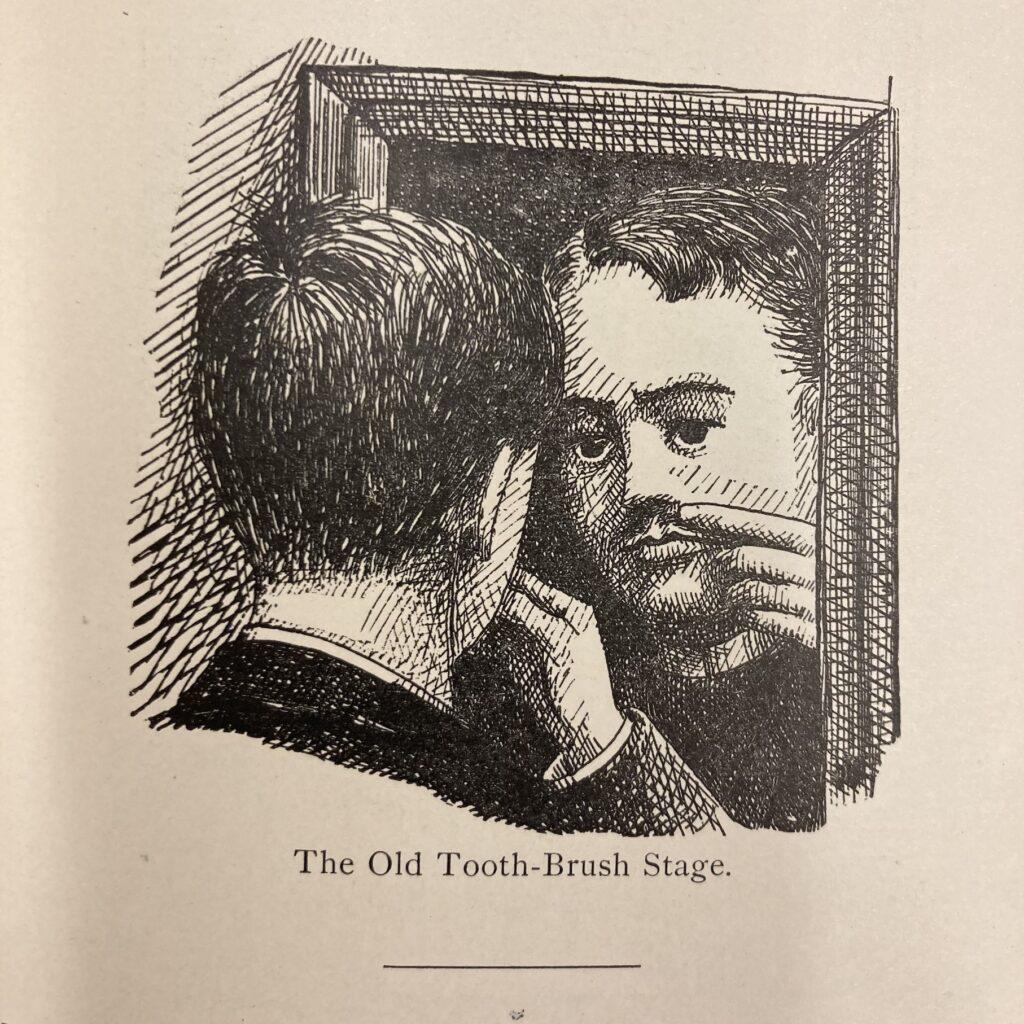

Right: A cartoon from the 1884 edition of The Bolt.

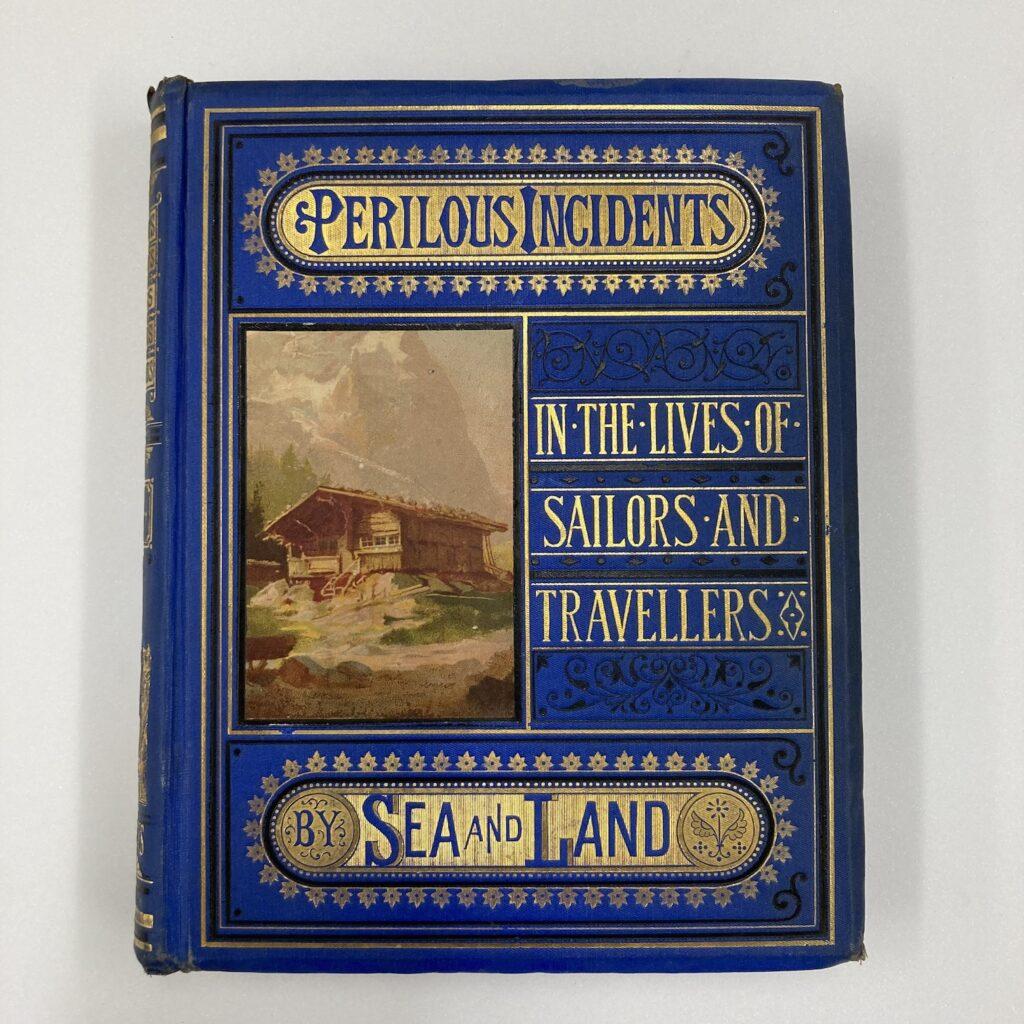

Center: Cover of Perilous Incidents in the Lives of Sailors and Travellers, published in ca. 1876.

Left: An inscription in Journal of the life, travels and gospel labours of that faithful servant and minister of Christ, Job Scott, dated 1797.

When people think of archivists handling valuable artifacts, rare books, and precious documents, they might imagine a white-gloved specialist delicately leafing through dusty files. Although white gloves, art, and antiquities often go hand-in-hand in the public imagination, the debate of whether white cotton gloves should be used within museums is much more fraught.

Specialists continue to discuss what kind of gloves are best for handling older and more fragile books and documents. However, the tide has turned against white cotton gloves in the past 15-or-so years. Interestingly, the use of cotton gloves to handle archival papers and books only arose towards the tail end of the 20th century, so the practice has been around for only a few decades. Nevertheless, in its short life, the practice has become lodged in the cultural conscience, despite archivists’ and librarians’ best efforts to correct the record.

The appeal of white cotton gloves is hard to deny. They serve as a visual shorthand for a particular strain of art historical professionalism and they have a certain flair that nitrile gloves, so often seen in clinical settings like labs and doctor’s offices, undeniably lack.

When I was an intern at a small art gallery the summer after I graduated from high school, I delighted in getting to put on my white gloves to move, hang, and even assemble art works. Whenever I put the gloves on, I immediately felt more professional.

However, the pitfalls of gloves were clear despite my deep-seated affinity for them. They rarely fit properly, which can make it more difficult to handle delicate works of art.

On one occasion, I had to assemble a work of art made of dozens of pieces of paper that needed to be nailed to the wall in a specific arrangement. Some of the pieces were just an inch or two long, and the thickness of the cotton gloves made it difficult to pick them up.

The same is true for handling archival paper or trying to turn the pages of an old book. The paper, which is often fragile or brittle, can easily tear or flake when mishandled.

Librarians and archivists at institutions like the Library of Congress and the National Archives in the United Kingdom have pointed out the downsides of cotton gloves in their own blog posts and publications. For one, there is no scientific evidence that the use of gloves, cotton or otherwise, actually protects paper. Natural oils in the skin only pose significant risks to materials like photographs, film, and ivory, and gloves are recommended when handling those.

However, cotton gloves are pretty much useless when it comes to any moisture. Wearing cotton gloves can make your hands sweatier, but cotton itself is too porous to create a barrier between a book or paper and the excess moisture being produced. The moisture also makes it even easier for the gloves to attract dirt, dust, and other particles.

In fact, gloves become dirty in the exact same way that hands can become dirty, and nothing about wearing gloves prevents the transfer of dirt in either direction.

In their 2005 article “Misperceptions About White Gloves,” Cathleen Baker and Randy Silverman also make the key point that assuming gloves are best for handling books and other material forgets the innate humanity of older books, which were printed, bound, collated, and otherwise assembled by people, not machines. Not to mention that after all of that, the books were read by people. Many of the books in the collection have stamps from other libraries, like the Mercantile Library, the Clinton Hall Association, and the Queens Borough Public Library. Still more have custom bookplates from private or semi-private collections. These books circulated for decades—the Mercantile Library, for example, began loaning books in 1821—before being donated to the Museum.

Many of the books in the collection are trade-specific, meant to be referenced and learned from, not sit untouched on a shelf. Their continued existence and readability is indicative of the fact that human handling of a book does not immediately degrade it. I’ve never opened up a book and found it covered in fingerprints, and it’s relatively uncommon to find a book where the inside pages are actually dirty. In many cases, I’ve found that even when the covers of a book are significantly deteriorated, the pages are in fairly good condition.

After hearing all of that, you might be wondering why gloves are still part of my daily routine since they seem to do more harm than good. However, while cotton gloves are safely off the table, the answer to the question of when—or whether—to wear latex or nitrile gloves is less cut-and-dry.

There are still a few situations where gloves made of a synthetic material like vinyl or nitrile are recommended. When handling an object that may pose some sort of risk, whether from mold, lead, or lingering chemicals, gloves are still recommended.

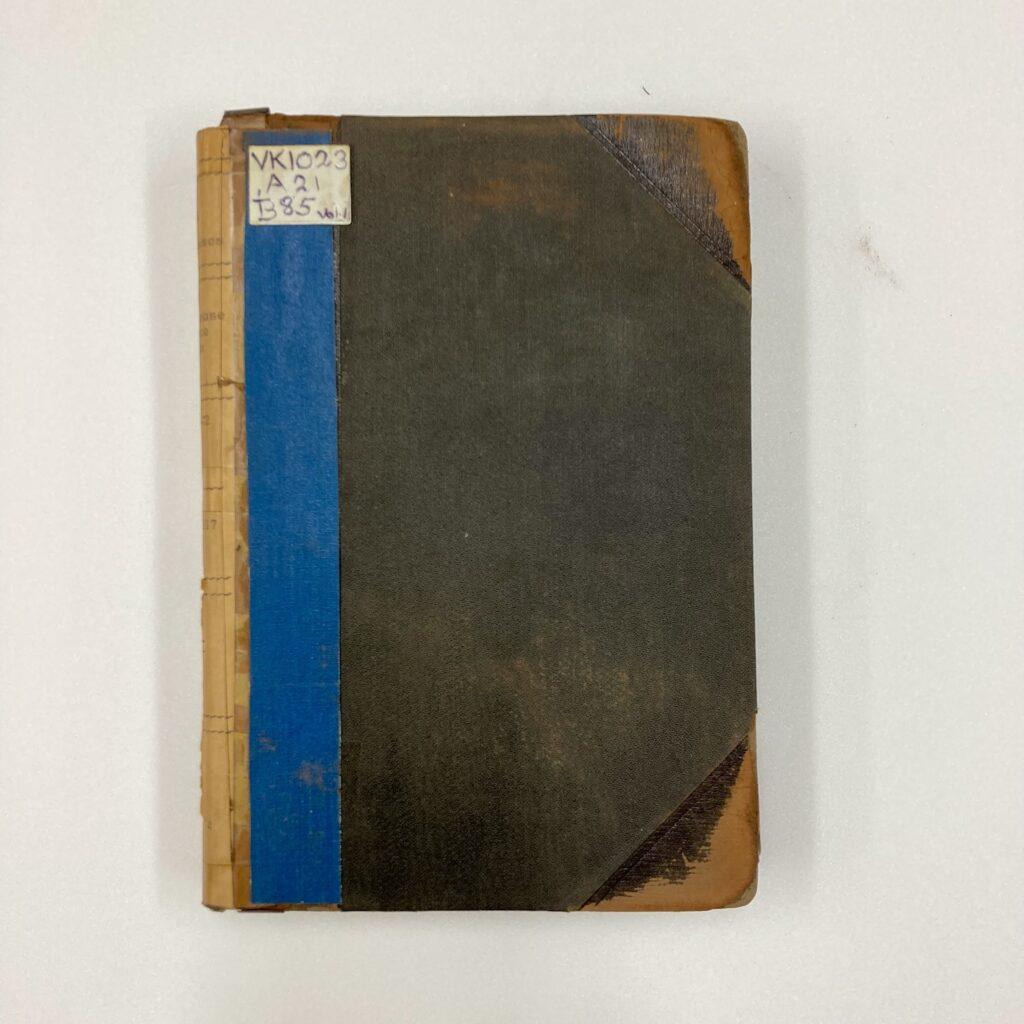

When working with books specifically, gloves are important for handling green books bound from the 1840s through the 1860s because of the risk they contain arsenic. To achieve a distinctive and eye-catching shade of emerald green, the Victorians turned to a compound containing copper acetoarsenite, otherwise known as arsenic. Tens of thousands of books are thought to have been bound with toxic fabric, so encountering one in a collection of books mostly from the 19th century is not out of the question. In all of these cases, the use of gloves protects the person handling the artifacts more than the artifacts themselves.

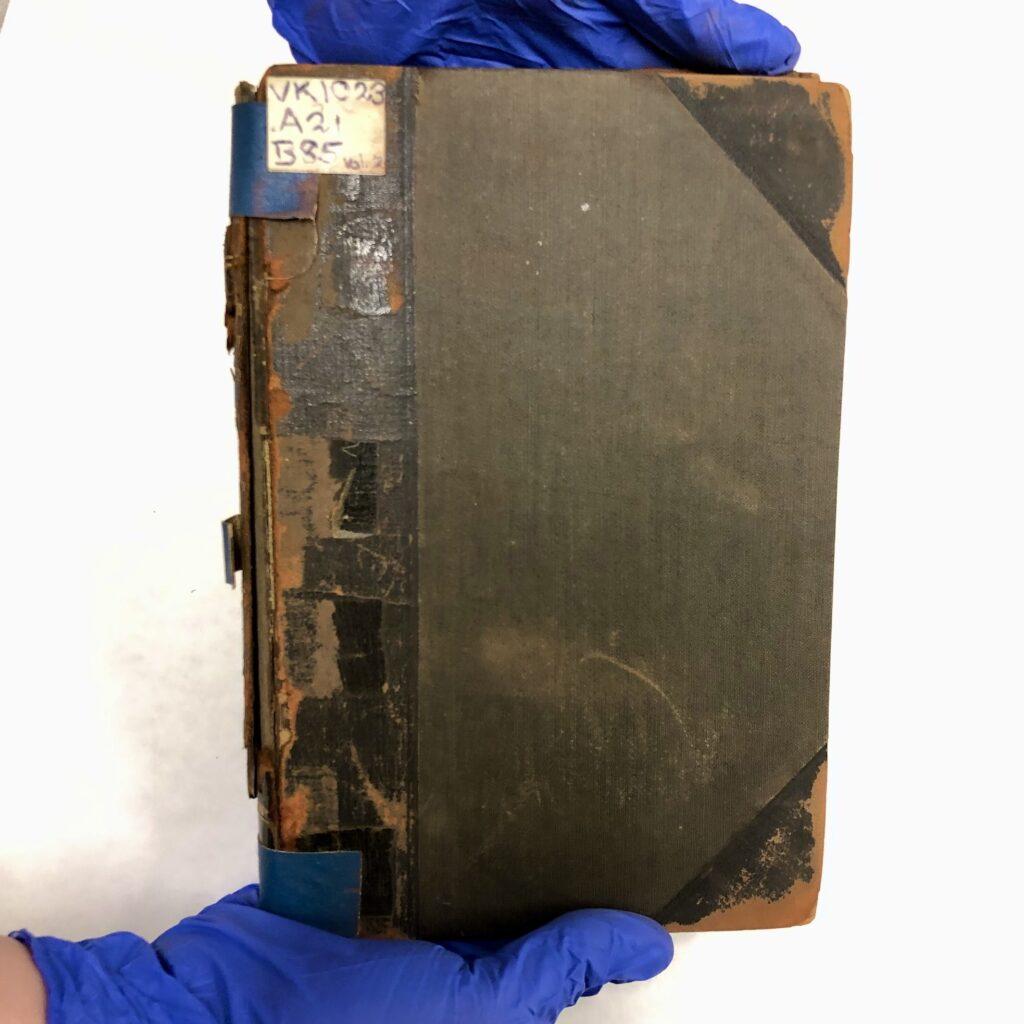

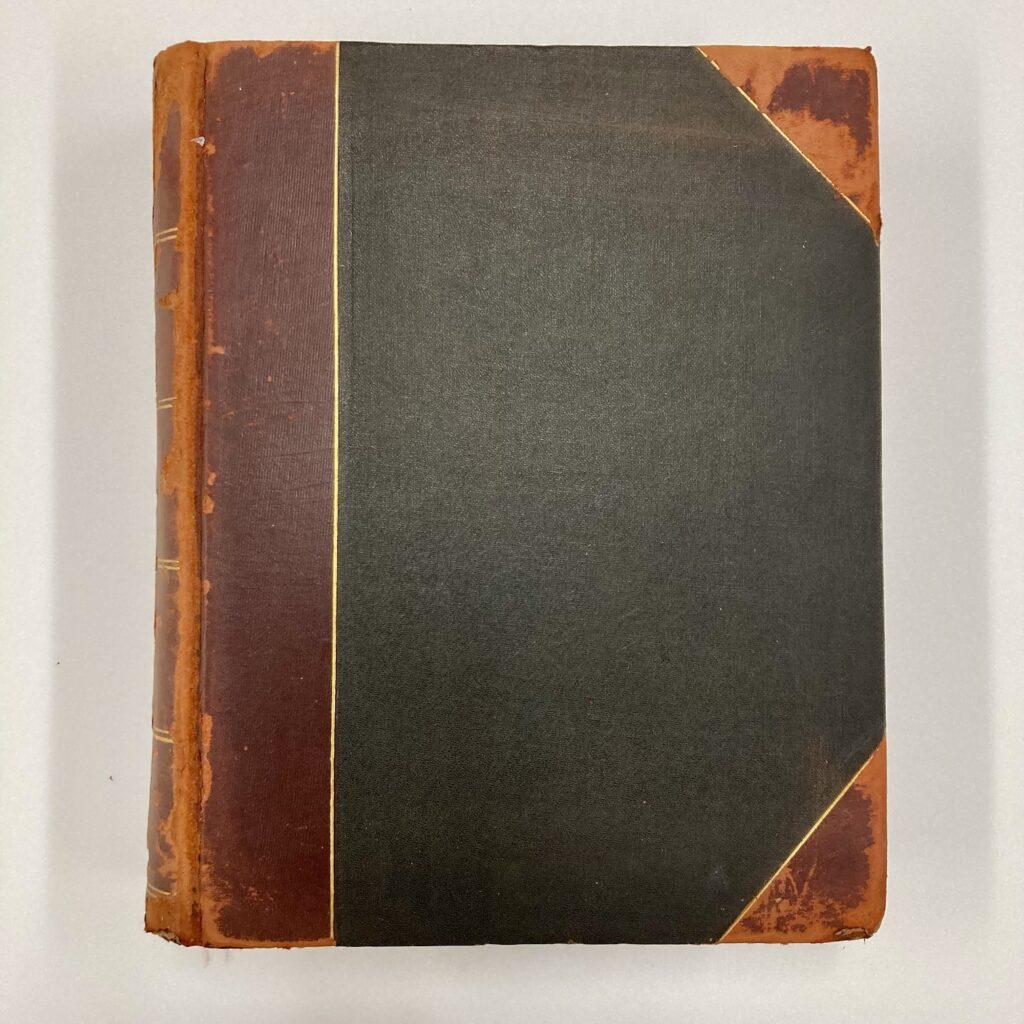

Examples of books with red rot. Red rot affects leather, not cloth binding. The books shown here have half or three-quarters binding, where the leather only covers the spine and a portion of the cover.

Beyond substances that can be actively harmful, there are some other times when gloves should always be worn. If you have nail polish on, for instance, gloves are worn to prevent flakes of polish from falling onto the material. Then, there’s the main reason that I put on gloves every day: red rot.

Dirt is a two way street. Many of the books I work with have some degree of damage, and that often includes red rot, a type of leather degradation that leaves trails of rusty-reddish, brown, or beige powder in its wake. Many of the books in the collection are wrapped in tissue paper, which prevents them from transferring red rot to the surrounding books and adds many fun surprises to the process of unpacking a box of rare books. To avoid accidentally staining my hands, clothes, and other books, I prefer to always wear gloves—and although I can’t say my clothes have always come out unscathed, my hands have.

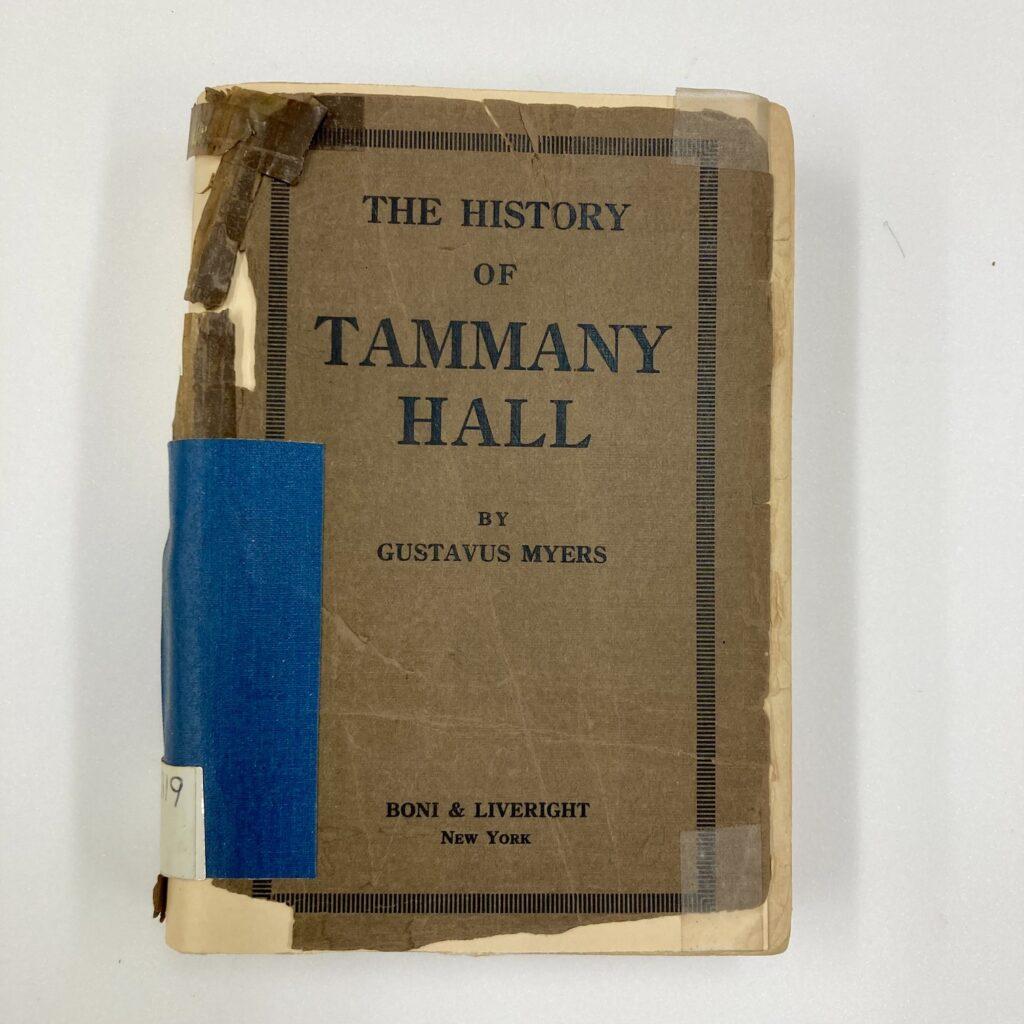

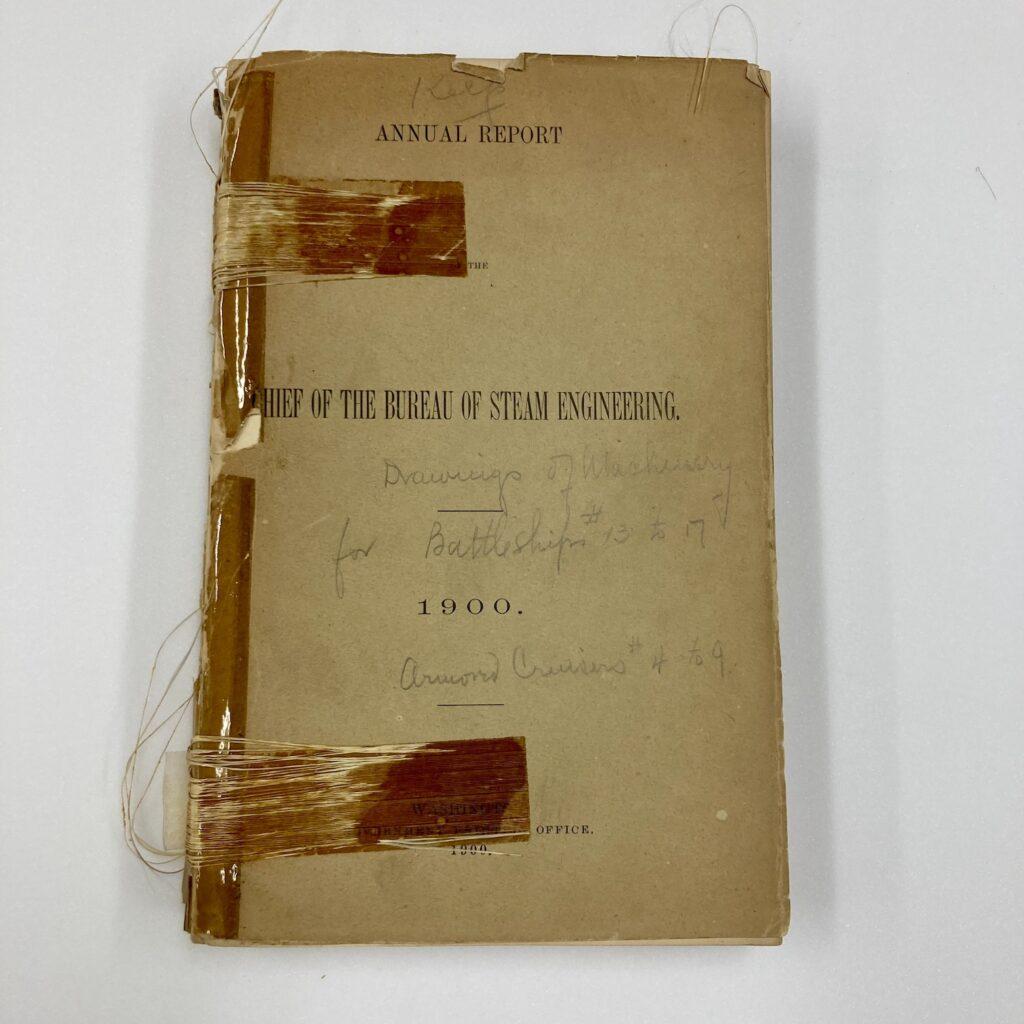

The arguments surrounding gloves are just one example of the ever-changing debate about best practices in book preservation. Among the rare books I’ve processed are examples of preservation practices that would no longer be preferable or even acceptable. Occasionally, books appear to have been re-covered at some point between publication and the present day, and I’ve even come across a few books quite literally being held together by tape.

In most cases I encountered, tape was used to keep the covers attached to the spine and text block of the book.

Much like white gloves, these attempts to repair books were presumably done with the best of intentions. As a temporary fix, they do keep the books readable, but they also permanently damage the book. One of the most important takeaways from the debate over gloves is that our understanding of how best to preserve and care for a collection is always changing.

While there are many books that would benefit from professional care by a conservator, books are also, by nature of their design and purpose, fairly resilient. For every book with a detached cover or brittle pages, there are several more that are mostly or completely intact. A relatively small percentage of books in the collection are designated as “In Need of Preservation.” Most are ready to be shelved as is, or with some protection like a tissue paper wrapping or a phase box. That book from 1797 I mentioned earlier? It was in better condition than some books from the 20th century that I’ve come across.

This is not to say that these books can be treated exactly like something you might find in a bookstore. As examples of past material culture, and due to the stories they can tell, these books have been identified as worthwhile to preserve for future researchers. However, white gloves are certainly not part of that treatment. Instead, a bit of common sense, an open mind, and a willingness to adapt to changing understandings of collection care and the unique needs of each book are the most important tools we have to work with.

Additional Readings and Resources

Baker, Cathleen A., and Randy Silverman. 2005. “Misperceptions About White Gloves.” International Preservation News, no. 37 (December), 4–9. https://www.loc.gov/preservation/about/faqs/ipnn37.pdf.

Chaletzky, Aaron D. 2022. “Take that you filthy red rot! | Guardians of Memory.” Library of Congress Blogs. https://blogs.loc.gov/preservation/2022/10/red-rot/.

“If Books Could Kill – A Short History of Poison Books.” 2023. UT San Antonio Health LibGuides. https://libguides.uthscsa.edu/news/March2023.

Sampson, Amy. 2023. “Handling historic collections: The gloves are still off.” The National Archives blog. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/handling-historic-collections-the-gloves-are-still-off/.

“Should gloves be worn when handling valuable collections? – Ask a Librarian.” 2021. Ask a Librarian. https://ask.loc.gov/preservation/faq/337286.

Collections Chronicles

Check out our bi-monthly blog where our collections team takes you behind the scenes and shares some of their work, inspiration, and more while highlighting hidden gems of history, the seaport, and our collection